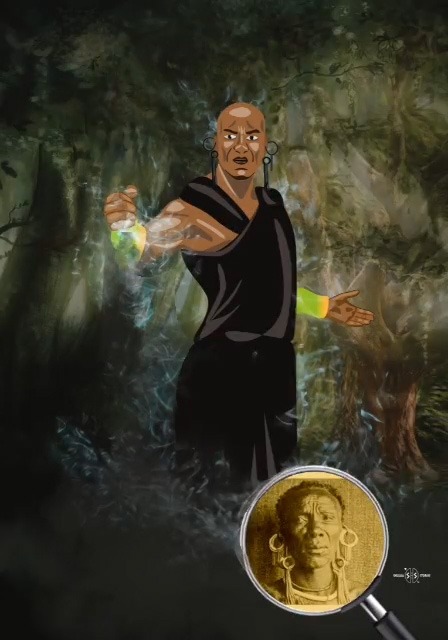

How Chief Karuri wa Gakure fought and won the smallpox pandemic in the late 1890’s

As Kenyans grapple with how to contain Covid-19, there is still the untold story of how Chief Karuri wa Gakure saved his people from smallpox — and how the pandemic reorganised modern day Kenya.

From it, we can pick some lessons as we go through one of the greatest challenges in history.

From 1892 or thereabouts, a smallpox pandemic hit parts of central Kenya, Nairobi, Ukambani, and Rift Valley — and how the administrators tackled it; at times to a point of losing hope or having suicidal thoughts is one of the biggest lessons that we have.

They not only quarantined people, then, but had them put under isolation to tame the spread. Those who didn’t died.

At one point, the Imperial British East Africa official Francis Hall — the man who was at the centre of it — sent a note of desperation: “This is the worst job I have tackled … this service now is hardly bread and butter.

In fact, if things go on as at present, we shall never be able to afford to get home on leave … living is so frightfully expensive, every other man in the service is head over ears in debt and the whole show is rotten from stem to stern. We want a good man at the helm. Until we get one, life is not worth living and I should be jolly glad to get out of it.”

NO LEADERSHIP

Hall was frustrated that there was no leadership in the fight against smallpox after London had transferred senior officials to Uganda.

But as smallpox decimated parts of Kikuyuland from 1895, one area on the slopes of Aberdares was spared. This was the Chief Karuri’s territory after he managed to quarantine his people by deterring entry.

For starters, Chief Karuri is the man credited with allowing the first missionaries in central Kenya — the Consolata Fathers, sent by Joseph Allamano, to settle in Tuthu in Murang’a County, after all it was one of the places that had sizeable population.

Historians agree that smallpox had killed so many people in southern Kikuyu — with most retreating to parts of Murang’a and Nyeri — that when the white settlers first arrived they thought the southern Kikuyu territory of Kiambu was previously unoccupied.

When missionaries arrived into Karuri territory, he not only provided them with land but allowed them to erect a church — and within 18 months, they had six stations in central Kenya.

The Consolata missionaries baptised him “Joseph” — a name he never used — and his wife “Consolata”.

A story is told that Karuri was supposed to be baptised together with hundreds of his followers on June 29, 1902 but a rumour was sparked in the territory that in baptism one was immersed under water overnight. Many skipped the event.

The pioneer missionaries in Tuthu included Fr Philip Perlo, whose diary records that Karuri was of Dorobo, Maasai and Kikuyu parentage. Others were Fr Thomas Gays, and Brothers Celeste Lusso and Luigi Falda.

Smallpox had continued to ravage the region as people moved.

“It was about this time that smallpox broke out in the country, and for the time being all my other troubles were relegated to the background,” recalled John Boyes, a renegade hunter who had married a Kikuyu girl and stayed in Murang’a. He also christened himself “King of the Wakikuyu”.

People did not take chance when a case of smallpox was noticed.

“We were having a shauri, when I noticed in the crowd an elderly man, a stranger to that part of the country, and a single glance was sufficient to show me that he was suffering from smallpox,” wrote Boyes in his diary.

Boyes not only asked the locals not to mix with him, warning that they would die if they did.

“They immediately stood away from him and said that I ought to shoot him which to their mind was the most natural precaution to prevent disease spreading.

“I told the natives that what they ought to do to avoid the infection, and arranged for an isolation camp to be built in which the man was placed, telling some of the people who lived nearby to leave food for him at a respectable distance.”

FOLLOWING RULES DIFFICULT

As with Covid-19, having people follow the rules is one of the biggest challenge.

The locals, according to Boyes, did not follow his instructions and the man left the isolation camp later on.

“Some days later, I was travelling through the country when I again saw the man in the crowd, and in great alarm I sent some of my own men back to the isolation camp with him. But it was too late. The disease had already spread to others, and I saw a lot of bad cases among people and though I tried to get all of them into isolation camps, it was practically of no use,” he wrote.

It is not clear whether Boyes was talking of a case in the Karuri territory — where he stayed or near Murang’a town where he became a bother to the locals.

What we now know is that the only place that escaped the smallpox epidemic was Chief Karuri’s territory.

Actually, it is recorded in history that the Tuthu area did not get a single case of smallpox because Chief Karuri deterred any foreigners from entering his village. Apparently, it worked. He poured some black powder across all footpaths leading to his village and spread a rumour that if “anyone looked at that poison, they died immediately”.

Nobody crossed that path and — unlike the Fred Matiang’i blockage of Nairobi, Kilifi and Mombasa, this was not manned but it worked.

While many villages were wiped out by smallpox, no case of smallpox occurred in Karuri’s village.

That was due to the precautions that Chief Karuri had taken very early before smallpox became a pandemic.

We also know that smallpox had been brought into the interior by travellers and traders — and later on by railway workers.

While some quarantine measures had been instituted upcountry, it was not so in Mombasa and in a diary entry dated August 15, 1899, Francis Hall, the founder of Murang’a Town complained: “They have sent us the smallpox from Mombasa. We luckily caught the later in time and by stringent regulations we have managed so far to keep it within bounds. There are about 100 cases in the isolation camp and about a dozen have died.”

But it appears from Mr Hall’s letters that Mombasa had failed to isolate people and in his diary entry he noted: “In Mombasa, I hear it is awful; cases of confluent smallpox walking about in the bazaar and every day the police pick up bodies in the streets. In one day, they picked up 57, yet nobody seems to care, and natives are allowed to come upcountry freely by train. It is time we had some strong man to boss this country; things are simply going from bad to worse and goodness knows where they will end.”

Among the people who had been quarantined due to smallpox were 12 CMS missionaries. The other notable person in quarantine was Canon Harry Leakey.

He wrote: “Leakey is the only old hand and he has brought a wife with him with him this time. I have seen three out of the six ladies and they are certainly a vast improvement on any previous samples of the genus. They are ladies and they seem very jolly …”

Cannon Leakey was the grandfather to Richard Leakey, the palaeontologist and former Head of Civil Service in the Moi government.

DECIMATED POPULATION

The 1899 pandemic was so bad among the Maasai and the Kikuyu that it decimated the population.

“Things were so bad,” Hall wrote. “I had to see smallpox corpses buried every day. With famine and smallpox, we are burying six or eight a day. One can’t go for a walk without falling over corpses.”

While Hall was fearful of contracting smallpox, which he had first noticed in southern parts of Mathira (then known as Konyu), and which had also seen the Maasai settle among the Kikuyu — he would later die of dysentery after he led a punitive raid on the people of Muruka in Murang’a. His fort in Mbiri was renamed Fort Hall (now Murang’a town).

But both Hall and Karuri are the two people credited for keeping smallpox at bay. In their own style, they quarantined people and isolated others. Those who listened survived.

It is the same thing with Covid-19: quarantine and isolation has worked from history.